Startup Win Conditions

IPOs, Acquisitions and the Roads in Between

You know how in the first Pokemon games you could see the path to Victory Road in Viridian City? That’s the purpose of this piece - to talk through the potential outcomes when starting a company. Obviously, people will say it’s best to keep your head down and focus on building and selling vs spending time thinking about exits. This is tautologically true and I would agree with that advice. You need to spend your time and energy building your team and collecting gym badges before you’re ready for the Indigo Plateau. But that doesn’t mean you don’t have a sense of the end goal - the potential win conditions for the journey on which you’re embarking.

One key takeaway for any founders or future founders reading this piece: you’re not building a tech business, you’re building a Business. There’s no real divide between finance and technology. Founders are capital allocators, whether they realize it or not. From day one, you’re allocating capital. You’re making decisions about how to deploy time, talent, and money. And once you’re allocating capital, you’re accountable to outcomes. The examples below - Google, Amazon and Mellanox, are tried and true stories of what it looks like to win by building around that mindset. I’ll be publishing follow-ups that unpack how today’s best startups are following similar playbooks and continuing to explore the theme of founders as capital allocators in my never ending quest to bridge the worlds of finance and tech. Stay tuned.

At a high level, it’s simple: you either

Go public

Get acquired (by another company or a PE fund)

Fail

There is a fourth outcome: operate indefinitely as a private company, generating enough cash to cover your lifestyle. But this is rare (and probably unrealistic) if you take institutional capital.

I should note the recent trend of companies staying private much longer than in the past, with liquidity available to employees, founders and investors through secondary transactions. The debate about the sustainability of liquidity via secondary and the overall trend of larger private rounds (dollar numbers that would have been massive IPOs not too long ago) is the topic of another article.

There is far more private capital than at any point in history, the network is perhaps more mature (and just following laws of supply and demand e.g. there is enough demand for Anthropic, Databricks, OpenAI, Stripe shares that these large rounds and secondary transactions can get done) the realities of going public force a different kind of scrutiny on a company and the current FTC regime has made it exceedingly difficult to get M&A deals across the line.

All that said, what’s the point of writing this? Well, I often get asked “what should a technical founder learn about finance to arm themselves when starting a company?” So this is just my two cents on how to keep the Pokemon League in the back of your mind as you build your team and collect gym badges. If you’ll allow me to be grandiose for a moment - I do also believe that healthy capital markets are a key component of a strong economy and business environment in the US (and across the world.)

So you started a company. You’re aware that you need to consider the potential exit scenarios to best prepare yourself for the journey. What might they look like?

The home run. The 5 star outcome.

You’re profitable AND growing like crazy. The north star for this situation would be Google’s IPO.

From $220k to $960m in 5 years and being profitable for 3 of them. You’ve proven your technology. You’ve built a world class team that’s aligned with your mission. You’ve found a proven method for getting distribution and capturing value and you’re looking for additional capital to do this at a greater scale. Google’s IPO should be studied for what an ideal company looks like at time of going public. Google is of course, one of the best businesses of all time, so it’s unlikely that many other companies will be able to chart a similar course but just because you won’t be able to play basketball like Michael Jordan doesn’t mean you don’t study his jump shot.

There are lots of other good examples of companies that were growing rapidly and either profitable or with a clear path to profitability. There (maybe) a few select types of business that just has no other way but to burn billions and billions in order to reach the scale necessary for their ultimate success. Uber pulled this off. But due in part to mis-aligned incentives, the growth at all costs mentality has become the norm and it seems that few companies reach the public markets already generating an operating profit.

There is no inherently right or wrong way. It’s up to you as the founder to understand the ROI of every decision you make. You can tell from reading his early shareholder letters that Jeff Bezos was fluent in this idea. He understood that the key driver of sales growth was going to be reinvestment in the business. And so it was marginally less important to show operating or net margins in the early years, when those dollars could be reinvested towards growing Amazon’s total sales.

The Almighty Merger / The Holy Acquisition

I was trying to relate each outcome to a civ win condition. IPO would probably be a domination victory. In a sense, an acquisition could be any of the others - cultural, science, religion etc. An absolutely unstoppable force of a company probably has no amount for which they would be acquired, but that doesn’t mean an acquisition is somehow a worse outcome. In fact, from a founder’s perspective, when you factor in time invested, it may even be preferable.

So why does a company get acquired? For various reasons and often a mix of a few key strategic factors -

Being a Strategic Fit

Acquiring the IP and Talent

Acquiring an existing customer base

Acquiring revenue synergies

Being a cultural fit

Case Study:

Nvidia’s 2019 Acquisition of Mellanox (2019, $6.9B)

Often an ideal acquisition will check multiple, if not all of these boxes to some degree. Mellanox was the perfect acquisition for Nvidia because it delivered strategic alignment, key IP + talent, customer expansion, revenue synergy, and cultural fit all in one deal.

People might not remember a time when Nvidia wasn’t the dominant leader in Data Center Products, but the segment represented much less of their business in 2017. At the time, there was a race to figure out what the post Moore’s Law world would look like. There was some consensus that as Moore’s Law slowed, performance gains would come from linking multiple chips together in high-performance computing clusters rather than relying on individual chip advancements.

This shift to distributed systems (like the ones that were being built by hyperscalers to offer their cloud computing services) significantly increased the need for high bandwidth / low latency networking solutions (with the challenge of number of instructions per chip solved by doing the computations in parallel, the focus shifted towards how fast / how much data you could send between nodes in the network and how reliable those connections were.)

Mellanox was the industry leader in high-speed interconnects, with InfiniBand and Ethernet solutions widely used in cloud and high performance computing systems. As enterprise computing environments continued to evolve towards the distributed systems model, Mellanox’s product suite was a clear strategic fit for Nvidia’s expansion further into the data center market.

Rather than developing an in-house solution, acquiring Mellanox allowed Nvidia to offer data center customers a fully integrated compute and networking package. This vision proved to be incredibly prophetic (and profitable) as high speed networking represents one of the major bottlenecks for computing in the AI era, and the combination of Nvidia GPUs + Mellanox Interconnects has become the industry standard for state of the art AI workloads.

It’s probably to the point where it’s taken for granted, but the massive performance improvements as well as a much lower total cost of ownership that came from the Nvidia + Mellanox synergies have definitely accelerated (and probably enabled to some degree) the major advancements in AI we’ve seen in the past few years.

The IP and Talent angle naturally follows from understanding how strong the synergies were with Mellanox as a strategic fit for Nvidia. Mellanox had deep expertise in networking silicon, high-speed data movement, and low-latency interconnects—a highly specialized field that few companies mastered. They had been building at this vision since 1999 and had acquired some key technologies themselves along the way. The engineering team at Mellanox was world-class, with a commanding lead both R&D and production for data center interconnects, InfiniBand, and Ethernet technologies. Nvidia didn’t need to build this expertise from scratch—instead, it acquired both the technology and the people driving innovation.

The story around revenue and synergies naturally follows as well. Nvidia saw a future where “The Data Center is the Computer” and being able to sell an integrated compute + networking solution to customers investing heavily in that vision of the future would position it well in a “picks and shovels for the gold rush” type of scenario (overused I know but is there really a better modern example of this in action?)

To put it into perspective, in 2019, when the acquisition was being finalized, Nvidia’s revenue was almost $12B for the year. Last quarter, their data center revenue alone was $39B. They are on track for more than $160B in sales for fiscal year 2026. That’s over a 13x on a $12B revenue base in 7 years post acquisition. That’s insane. It should be in the business school dictionary next to the definition of revenue synergies. An extraordinary example of revenue synergies in action.

Also to zoom out, Nvidia’s path to dominance in data centers was by no means a given. Nvidia was worth $144B at the end of 2019, a little more than half of Intel’s $260B market cap at the time. Looking at the above financials for Nvidia and Mellanox at the time of the acquisition respectively, it is clear that great CEOs see the potential far beyond a sum of the current revenue bases. As the world increasingly depends on the most advanced supercomputers to power AI, a combined revenue base of $13B at the time of the purchase has grown into one of the biggest and most important companies in the world.

The customer base was an important but less crucial factor of the acquisition. Nvidia already had relationships with its key customers (AWS, Azure, Google Cloud etc.) and while Mellanox did have some key relationships that Nvidia would inherit (Dell, HP, Microsoft, Oracle was once a 10% shareholder, to name a few) the main synergy in terms of customers was being able to sell a much improved, integrated product to existing customers. Importantly, Nvidia was now a one stop shop for crucial enterprise (and now AI) computing infrastructure.

In terms of a cultural fit, both Nvidia and Mellanox were led by highly technical CEOs (Jensen Huang at NVIDIA and Eyal Waldman at Mellanox) who prioritized deep R&D over short-term market pressures. Their cultures valued technical excellence—rather than focusing on rapid iterations, they built fundamental technology for long-term impact.

Neither company optimized for short-term product cycles. Instead, both invested in high-risk, high-reward innovation that would define computing infrastructure for the next decade.This shared long-term philosophy made the integration smooth—Mellanox didn’t have to adjust to a radically different corporate mindset.

Unlike many acquirers that aggressively merge teams, NVIDIA allowed Mellanox to maintain independence while aligning on strategic goals. This helped retain key engineering talent, ensuring that Mellanox continued innovating within NVIDIA rather than experiencing brain drain. Cultural alignment is as important as financial synergy—misaligned cultures can derail even the best deals. If an acquirer respects your company’s autonomy and vision, it leads to better integration, talent retention, and long-term success.

There are other great examples that come to mind for each category. Facebook buying Instagram and Google buying Youtube are great examples of companies buying a startup for strategic fit. Apple’s acquisition of NeXT and Google buying DeepMind are two examples of acquisitions for IP and Talent (of course, in almost every case, there are multiple reasons why an acquisition is made.) Microsoft buying LinkedIn, Amazon buying whole foods and Facebook buying WhatsApp come to mind when thinking of acquisitions that bought a customer base along with the company. Disney buying Pixar is a great example of both revenue synergies and a cultural fit. These aren’t rules that are set in stone or boxes that an acquirer checks when diligence a company, but hopefully a helpful framework for understanding the various reasons behind an acquisition.

Alignment and Incentives

From capital formation to business development and growth to exits and beyond, there are a million moving parts but one of the most important things is understanding alignment. If you raise institutional capital (venture money) it’s helpful to understand their incentives. They raise a fund to invest in companies and eventually have to pay back their own investors. They need companies to have liquidity events in order to generate cash and return it to their investors (and to renovate the kitchen in the Marin house.) The better the companies do, the better the investors do. The downside of this model is most (99%?) startups fail. So they need really big outcomes to generate an above market return on their fund. Not in every case, but often this will skew their deployment of capital towards companies that have a chance at these kind of outcomes. Again not in every case but this also informs their advice to founders - go big or go home. Raise more. Grow faster. Burn $1B for the chance to become a $10B+ company.

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. If you become a unicorn or decacorn or a hundred billion dollar corn, both you and your investors will (more than likely) get rich. The downside is that it doesn’t really leave room to exist somewhere in the middle (what some VCs call “lifestyle businesses”(derogatory).)

One way to generate that liquidity is going public. We can talk for hours about the “why” this isn’t happening as often as it used to or what it says about the “health” of capital markets but the simple explanation seems to be a lot of deals get done at sky high multiples in private transactions that wouldn’t hold up vs public market comps. Going public is probably what your goal should be as a founder. If you want to build a world changing business, a low cost of capital is pretty helpful for doing so and there’s an argument to be made that’s there’s no better position for a company to be in than being a trusted public company.

I should zoom out for a second again - one of the goals with Inevitability Research is to dispel the false dichotomy of business vs tech. Or at least blur the lines. If you start a company you need to build and sell. Can you be exceptional by focusing on one aspect vs the other? Probably. But I think the ideal model of a founder is Jeff Bezos (clearly I stan,) who seems to have harnessed both business and tech and used this combined knowledge as a force that drove Amazon to be one of the most successful and incredible companies of all time. Reading his early shareholder letters probably has a higher ROI than getting an MBA, especially for a tech founder looking to grow a durable business.

The other way to generate liquidity is via being acquired. It could be a strategic acquisition by a company looking to expand into the market you’ve captured, or by a private equity fund that specializes in companies like yours. There are various outcomes and transaction structures - ranging from all cash, no earn outs or vesting (so if it’s a $1B acquisition, the billion dollars is paid in straight cash to the current shareholders) to deals where more of the purchase price is paid in stock of the acquiring company and may require the founder to stay on and “earn” some of the compensation via achieving milestones set in the transaction. It may be the case that the acquisition is the most beneficial option for you as a founder, and you get to continue to run your business almost as if it was an independent startup but with the resources of a bigger company. The current trend to note is that there is a considerable amount of antitrust scrutiny aimed at Big Tech and this has made it pretty tough for companies with lots of cash and valuable stock to use it for acquisitions.

Another aspect of the alignment goal is your employees. Chances are you can’t pay market rate salaries for early employees, so you compensate them with equity. This is a big risk on their part given the average probability of success of any given startup and the time to exit for the ones that do get to a liquidity event. Astronomical valuations give the appearance of momentum and success but the number really doesn’t mean anything to an employee unless they’re able to trade their equity for cash. Just like you can’t eat IRR, you can’t buy a house with paper wealth.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, your task as a founder is balancing the long term vision with the countless decisions you have to make everyday to make your company successful. You have to be able to see things from a 30,000 foot view and put boots on the ground so you know what’s happening in the trenches. You have to know someday you’ll trek through victory road to face the elite four but still take it one battle at a time. One level at a time.

Understanding your startup’s win conditions doesn’t mean obsessing over the endgame. It means staying aware of the terrain: what capital you take, who you align with, and how those choices shape your eventual outcomes. Whether you IPO, get acquired, or chart some less common route, the founders who win tend to be the ones who know what game they’re playing. And why. Both a live player, and a student of the game.

As always, thanks for reading and I look forward to hearing your thoughts! See you again really soon.

Appendix: Bezos Shareholder Letter, April 2005

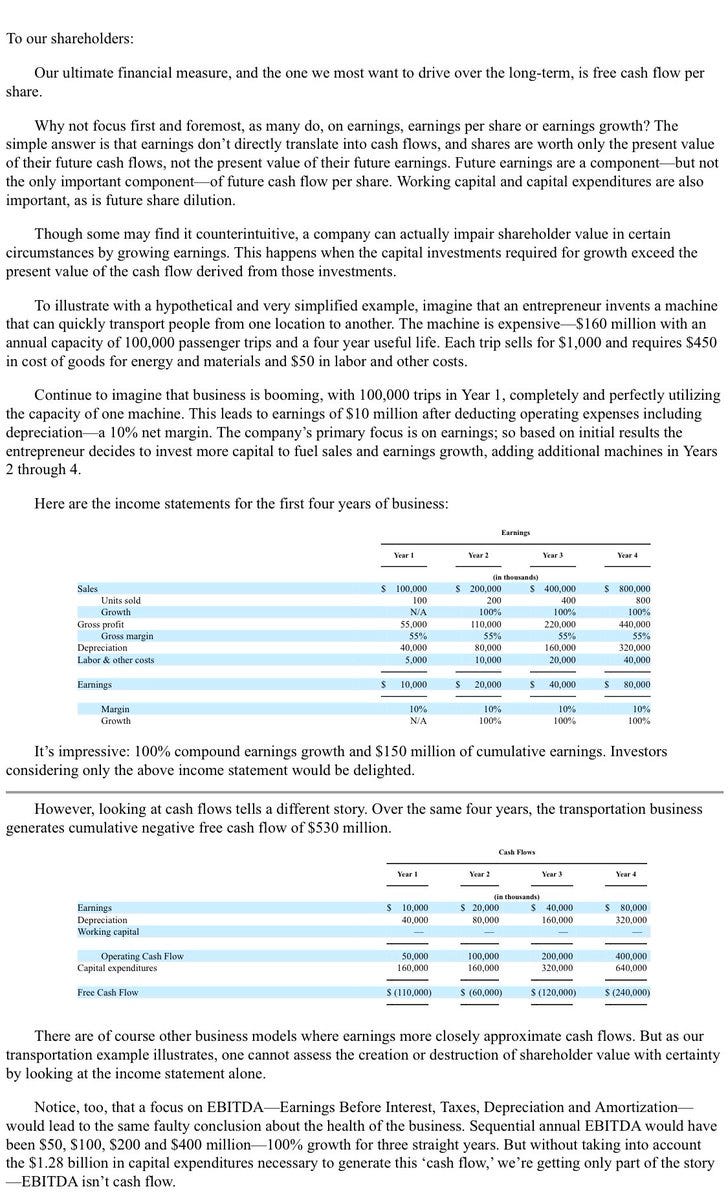

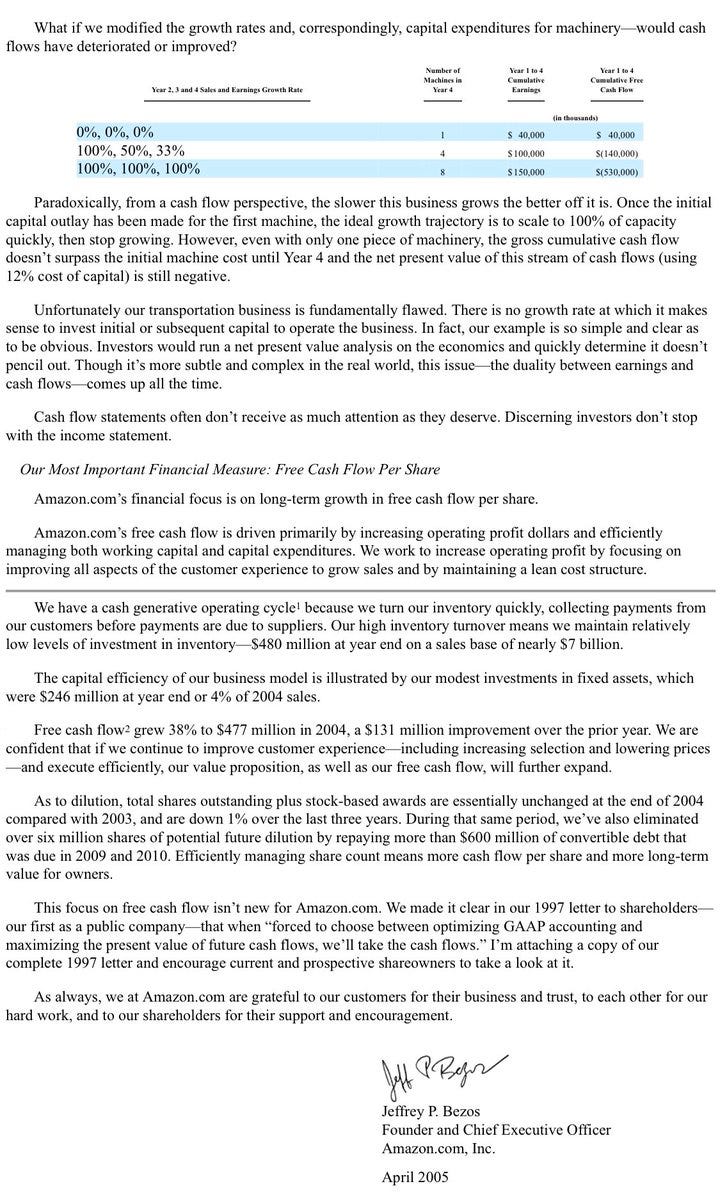

Below is one of my favorite letters from Jeff Bezos (included in the linked tweet but also wanted to share here) where he fluently demonstrates his understanding of the importance of growing FCF/share and how it relates to Amazon’s strategy. An understanding of key financial metrics and the mechanics that drive them are essential for any founder looking to build a great business that has a model durable enough to succeed as a public company.

great piece, Sophie. i’d add that when founders think like capital allocators, they see giving up some ownership as using that money to grow the company, not just losing part of it. more like a cheat code.

Thanks for writing this. Mellanox is under-discussed. 💚 🥃