The Price of Time Review

Are those who don't learn from history doomed to repeat it? The Price of Time documents "the real story of interest" in incredible detail and makes for an amazing read.

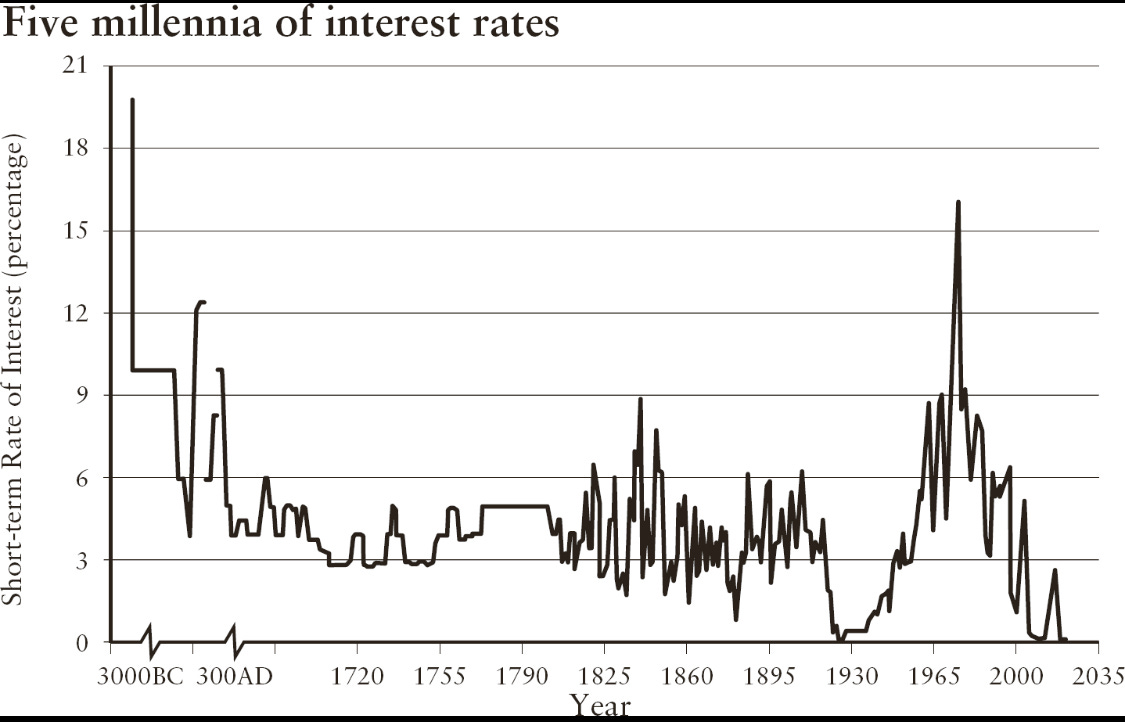

How do we trace the roots of our modern world? “The Price of Time” by Edward Chancellor explores the history of interest but beyond just the invention of money & credit (credit/money/interest certainly deserve a place on the list of most important inventions of all time), Chancellor explores the implications that interest rates have for the economy and the world as a whole. Crucial to Chancellor’s exploration is the idea (put forth by Knut Wicksell) that there may be a “natural” rate of interest (where the economy would function in the most optimal way, referred to as ‘R squared’) and that prolonged deviations from this natural rate can cause some weird stuff to happen. Perhaps most relevant to readers today, is what happens when interest rates are (perhaps artificially) held below the natural rate for too long. Chancellor documents historical eras where central bank policy was similar to recent periods of “ZIRP” and there are striking similarities to our modern world throughout his historical examples. The same animal spirits that were present in recent tech bubbles permeated life when John Law was shilling shares in the Mississippi Company in the 18th century, for instance, and Chancellor vividly recounts past bubbles in both an entertaining and educational way. It doesn’t take long to notice that long as there’s been interest rates, there’s been bubbles, and they tend to form when rates are low as investors look elsewhere for a satisfactory return (and as is well documented with lots of different examples in the book, low rates often directly or indirectly lead to a speculative mania that ends in a financial crisis.) While Chancellor does a good job of astutely documenting previous eras of central bank policy, as the book progresses, one can’t help but feel his bias against prolonged periods of easy monetary policy & low rates creep into his prose. Regardless of any personal views he may hold, “The Price of Time” is a fantastic and insightful read. Relevant to folks in finance where interest rates are explicit inputs in decision making models and to people in other industries were monetary policy decisions are felt more implicitly but affect the overall economic climate nonetheless.

Chancellor is a fantastic writer & a world class economic historian. The book is filled with anecdotes & stories stretching as far back in time as the Babylonians & Sumerians all the way to recent monetary policy responses to financial crises like in 2008. An astute reader might come away from learning about financial history thinking that crises are a feature not a bug, of the banking system & economy, considering how often they occur. Understanding this, and understanding that modern policy makers see lowering interest rates as the key tool to restart a stagnant economy amidst a crisis, are crucial to understanding what I believe to be the crux of Chancellor’s frameworks/worldview. In essence - the way the banking system is set up leaves it vulnerable to the booms & busts of credit and economic cycles, and while having a central bank as a “lender of last resort” can certainly soften the vicious spirals that take place during extreme panics & bank runs, interest rates that stay below the “natural rate” for too long have some nasty second and third order effects that sometimes take a while to show up in the real economy. And often by the time they do, policy makers must combat inflation by raising rates and potentially inducing a recession, which causes the economy to stagnate or contract and eventually leads to the central bank needing to lower rates again in order to stimulate demand. Chancellor expresses the view that central bankers have become “addicted” to low interest rates and presents compelling evidence for the perils that befall an economy with such an addiction.

The book poses some important question about the state of modern economics -

Why has productivity declined in recent years despite all the technological progress that’s been made?

Is the love affair between modern central bankers and low interest rates partly responsible? What other perils might this addiction lead to?, and what lessons can we glean from historical anecdotes of previous boom/bust cycles, financial crises & speculative manias?

Chancellor draws from lots of economic research including William White and Claudio Borio from the bank of international settlements (the central bank’s central bank) to make the argument that prolonged periods of low rates lead to some not so great stuff -

Some of the negative effects of artificially low rates -

Rates below r^2 drive capital into projects with lower than expected returns

Low rates artificially inflate asset prices

The increasing financialization of the world’s economies

Companies that should otherwise go under can stick around thanks to cheap borrowing (forest fire analogy)

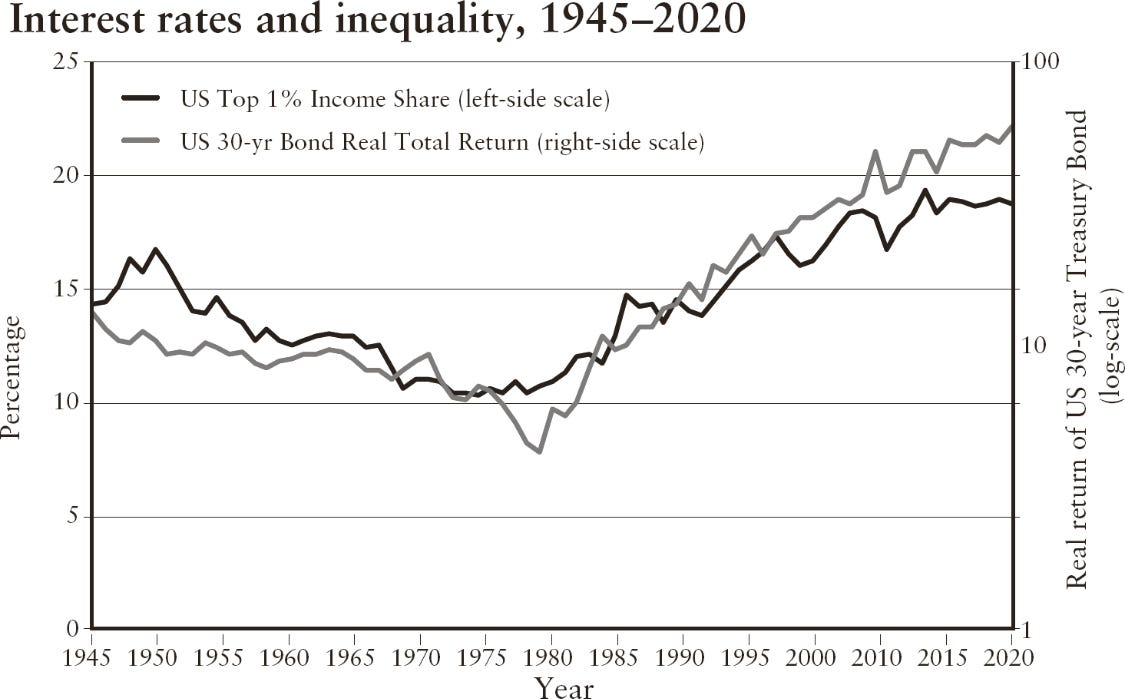

Growing wealth disparity/widening wealthy gap as inflated asset prices favor asset owners

Manufacturers push productivity further into the future and supply chains lengthen

Low savings rate hurts retirees

Low rates increases present value of liabilities for those that must manage assets & liabilities (banks, insurers, pensions etc.)

Widening wealth gap may indirectly lead to increase in authoritarianism & populism

For clarity, I tried to use block quotes (blue bar on the lefthand side of the screen) for instances where I used a quote that itself was used in the book and pull quotes (the ones with line breaks and italics) for instances where I used an excerpt from the book.

The book begins with a recollection of a debate between Pierre-Jospeh Proudhon (1849), an anarchist who believed that “property is theft and so is interest” and Frederic Bastiat, a free trade advocate who maintained that interest was a fair reward for a mutual exchange of services. The lender is providing the use of capital for a period of time, and as the books title suggests, time has value.

“Time is precious. Time is money – Time is the stuff of which life is made.’ It follows that interest is ‘natural, just and legitimate, but also useful and profitable, even to those who pay it’. Far from depressing output, capital made labour more productive. Far from stoking class antagonism, Bastiat believed that capital benefited everyone, ‘particularly the long-suffering classes’”

This debate is a fitting introduction for the theme that underscores the book - is there a natural rate of interest? If so, how might it be determined? And what happens when the actual interest rate deviates above or below the natural rate?

In Chancellor’s own words -

“The argument of this book is that interest is required to direct the allocation of capital, and that without interest it becomes impossible to value investments. As a ‘reward for abstinence’ interest incentivizes saving. Interest is also the cost of leverage and the price of risk. When it comes to regulating financial markets, the existence of interest discourages bankers and investors from taking excessive risks. On the foreign exchanges, interest rates equilibrate the flow of capital between nations. Interest also influences the distribution of income and wealth. As Bastiat understood, a very low rate of interest may benefit the rich, who have access to credit, more than the poor.”

The book is divided into three parts-

The first explores the history & origins of interest.

The second examines how “low rates beget lower rates” and the consequences of rates below the natural level. the second part looks at the run up to & policy responses after the great financial crisis in 2008.

The third discusses how rates affect global macroeconomics, capital flows & emerging markets.

“The Price of Time” is a fascinating read that is as educational as it is entertaining and if you’re interested in financial history or just curious where the ideas came from that have shaped our modern modern world of interest & money, I can’t recommend it enough. If you enjoyed my brief summary in the first part of this article, I have included some quotes and passages from the book in the sections below. These are parts of the book that I believe to be core to Chancellor’s thesis that central banker’s are addicted to low rates and they provide vivid historical context of examples of credit cycles in the past that are perhaps frighteningly similar to one’s we have seen in recent years. I include some examples from part 1 of the book (the historical section) and give a brief summary of parts 2 and 3 followed by a conclusion. If you enjoyed the brief summary above I think you will find the passage and quotes to be interesting and thought provoking and may even inspire you to read the book. If you decide to read the book based on my review please let me know! Don’t hesitate to reach out here or on twitter.

Examples from Part 1

The book begins by documenting the long history of interest, all the way back to the Babylonians, Mesopotamians and Sumerians, who would loan one another farm animals and seeds and expect interest in return. Irving Fisher wrote:

“Nature is, to a great extent, reproductive. Growing crops and animals often make it possible to endow the future more richly than the present. Man can obtain from the forest or the farm more by waiting than by premature cutting of trees or by exhausting the soil. In other words, Nature’s productivity has a strong tendency to keep up the rate of interest.”

Stone tablets from this era are some of the earliest documentation of humans transacting with one another on credit. If the borrower was unable to repay the loan, labour was often accepted by the lender as a form of interest payment. Perhaps of interest is that in ancient Babylonia, they used the same word (“mas”) to mean both interest and rent. This extends to modern German where “zins”, the word for interest, is derived from rent, continuing the ancient connection between interest and rent. The book documents how compound interest was invented in Mesopotamia and how debt crises were common as a result of the compounding interest creating an unsustainable burden for borrowers. It mentions how the earliest known set of laws, Hammurabi’s Code, was extensively concerned with how to regulate interest.

“The emergence of interest to incentivize lending is the most significant of all innovations in the history of finance,’ writes the financial historian William Goetzmann. This point is well made. Finance allows people to transact across time. The farmer borrows barley to sow his fields but must wait until harvest before repaying the debt. Industrial processes – even the light crafts-based industries of the Ancient Near East – require time in production from raw materials to the sale of finished goods. A text from third-millennium Mesopotamia shows that the preparation of cloth took over a year. Foreign trade consumes a lot of time. When capital is tied up in industry or trade, the interest charge bears some connection to the time used in production.”

There are many examples of cultures and religions that looked down upon “usury” and took the view that charging interest was wrong and even perhaps evil, but the “usury is evil” argument lost out to to the “time is the most important asset” argument put forth by Seneca:

Seneca’s notion that time is man’s most precious possession resurfaces in the Italian Renaissance in the writings of the architect and humanist Leon Battista Alberti (1404–72). In his Libri della Famiglia, composed in the 1430s, one of Alberti’s characters instructs on the proper management of time: ‘for I would sooner lose sleep than lose time, that is, than let the right moment for doing something slip by. ’17 Fernand Braudel writes that Alberti signals a shift from the earlier Scholastic view, when ‘time had been considered as belonging to God alone; to sell it (in the shape of interest) was to sell non suum, what did not belong to one. But now time was once more becoming a dimension of human life, one of man’s possessions which he would do well not to waste.’

The fist part explores varying views on “what” exactly determines the interest rate, including thoughts from David Hume, John Locke and Adam Smith amongst others.

“How the level of interest rates is determined remains one of the most perplexing problems in the field of economics. Some believe that the interest rate is derived from the returns on real assets – the surplus yielded by farmland, the profitability of an industrial concern and, more generally, by productivity growth across the entire economy. Others attribute it to the rate of population growth and to changes in national income (the annual change in GDP being derived from changes in population and productivity). Some maintain that the rate of interest reflects society’s collective impatience or time preference, while still others claim that interest is influenced primarily by monetary factors.”

Some other memorable quotes from Part 1:

“Interest is, as it were, human impatience crystallized into a market rate.”

- Irving Fisher

“Interest – the time value of money – lies at the heart of valuation. At the turn of the eighteenth century, the brilliant Scotsman John Law wrote that ‘anticipation is always at a discount. £100 to be paid now is of more value than £1,000 to be paid £10 a year for 100 years.’67 By discounting the future cash flow generated by a stock, bond, building or any other income-producing asset, interest allows us to arrive at its present value.”

- John Law

“If interest rates are kept below their natural level, misguided investments occur: too much time is used in production, or, put another way, the investment returns don’t justify the initial outlay. ‘Malinvestment’, to use a term popularized by Austrian economists, comes in many shapes and sizes. It might involve some expensive white-elephant project, such as constructing a tunnel under the sea, or a pie-in-the-sky technology scheme with no serious prospect of ever turning a profit.”

- Friedrich Hayek

“What the stated Rate of Interest should be in the constant change of Affairs, and flux of Money, is hard to determine. Possibly it may be allowed as a reasonable Proposal, that it should be within such Bounds, as should not on the one side quite Eat up the Merchant’s and the Tradesman’s profit, and discourage their Industry; nor on the other hand so low, as should hinder Men from Risquing their Money in other Men’s Hands, and so rather chuse to keep it out of Trade, than venture it upon so small profit.”

- John Locke

Part one also covers the various and extensive historical debates about who benefits from low/high interest rates and the effects that rates have on the real economy.

Examples of Historical Bubbles

Mississippi Bubble

One of the most fascinating and relevant stories is that of John Law. The son of a goldsmith, Law would lose a fortune gambling and then make it back. In 1694, he was be condemned to hang for killing another man in a duel but escaped prison before his execution. He would later go on to found The Mississippi Company, be named France’s Minister of Finance and found the French Central Bank.

“The fugitive Scot displayed novel insights about the nature of money. Money, he said, did not derive its value from precious metals, as people like Locke believed. Rather, money was simply a yardstick of value; or, as he put it, ‘Money is not the Value for which Goods are exchanged, but the Value by which they are exchanged.’5 This clever switching of the prepositions – by in place of for – amounted to a monetary revolution. In essence, he was saying that since money lacked intrinsic value it need not be backed by gold or other precious metals.

A constant theme in Law’s writings is that trade depends on the circulation of credit, and that credit was ‘only lost by a scarcity of Money’.6 Here Law anticipates later monetarists. He argued that prosperity could be achieved by establishing a bank that issued paper money, collateralized with land rather than gold and silver. By severing the link between money and precious metals, Law opened the possibility of a managed currency.”

Law, influenced by the Bank of England’s issuance of paper notes backed not by gold but by claims on the public credit, wanted to convince the French Regency to establish a central bank. The finances of French royalty were in a tough situation following the wars of Louis XIV with debts amounting to over double France’s total annual output and tax revenues that were insufficient to cover the interest payments. Law had the ambitious (and perhaps familiar) idea that the Central Bank of France could print money in order to monetize it’s debt. He believed that interest was determined by the supply of money and that by increasing the money supply, the national bank could bring about a reduction in interest (one of the earliest instances of the “money printer go brrr meme”).

“An abundance of money which would lower the interest rate to 2 per cent would, in reducing the financing costs of the debts and public offices, etc., relieve the King. It would lighten the burden of the indebted noble landowners. This latter group would be enriched because agricultural goods would be sold at higher prices. It would enrich traders who would then be able to borrow at a lower interest rate and give employment to the people.”

-John Law, presenting to the French Regent in 1715

In modern language, Law was suggesting that a central bank could reduce interest rates by printing money; that this would alleviate the position of heavily indebted borrowers (in this case, French nobles), create jobs and revive the economy. At the same time, the cost of servicing government debt would fall and deflation come to an end. In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, the world’s central bankers acted with similar intentions.

The Regent’s Council initially rejected Law’s proposal but eventually The General Bank opened in 1716 and received an edict from the Regent making its bank notes legal tender for taxes. A year later, Law took control of a company that possessed monopoly trading rights to French Louisiana (an area which at the time covered roughly half the land in the United States. He then merged his business with other French trading companies and established The Mississippi Company as the entity that controlled the various interests. Law wasn’t done however. In 1719, he set up a deal for the Mississippi Company to take over the entirety of France’s national debt in exchange for an annual payment. Law’s scheme was to allow creditors of the French government to exchange their bonds for shares in the Mississippi Company.

Shares of the Mississippi Company were issued at 500 livres and 3/4 of the subscription could be paid for with government debt. In 1718, the General Bank was renamed “The Royal Bank” and a small but crucial change was made to the nature of their bank notes. The new notes were denominated in the unit of account, the livre, instead of gold, removing any restriction on the amount of money that could be issued.

So what happened next? Well, if you followed the market in 2020/21, you probably have an idea. During 1719, shares in the Mississippi Company rose by 20x and peaked at 10,000 livres. If you had bough the initial issuance (essentially the IPO) you made 40x your money in a couple years. Their was a new word coined in France “millionaire” to describe the people who had made their fortunes off of the share price appreciation. The speculative mania that began in France soon spread to all of Europe, and for a brief moment in time, The Mississippi Company probably commanded a greater share of the world’s investment capital than any company in history. Law appeared a genius. His share in the company (by his own calculations) made him the richest person who ever lived. It would come crashing down almost as spectacularly as it was built up.

“In the short-term, Cantillon averred, a national bank could drive down interest rates by purchasing government debt with newly printed money. Expectations of further declines in interest rates would induce the public to acquire bonds, further lowering market rates and raising the price of securities. Such banking operations were fraught with risk, however. The economy would prosper only as long as the extra money balances, created by the note issues, remained trapped within the financial system: ‘The excess banknotes, made and issued on these occasions, do not upset the circulation [i.e. produce inflation], because being used for the buying and selling of stock [i.e. financial assets] they do not serve for household expenses and are not changed into silver.’50

But once the money escaped into the wider economy, consumer prices were bound to rise.”

-Richard Cantillion, Parisian Banker

“Delusion lies in the conception of time. The great stock-market bull seeks to condense the future into a few days, to discount the long march of history, and capture the present value of all future riches. It is his strident demand for everything right now – to own the future in money right now – that cannot tolerate even the notion of futurity – that dissolves the speculator into the psychopath.”

-James Buchan

Whether during the Mississippi Company bubble of 1719, the South Sea bubble of 1720 or the tech/telecom bubble of the 1990s, speculative manias exhibit similar characteristics. Years of future returns are pulled forward as speculators rush to bid up shares only to later realize there will not be any “real” wealth created until they can cash out there shares, which of course requires selling their shares to someone else (the “greater fool” theory - you’re not investing based on confidence that the intrinsic value of the underlying security will appreciate, you’re investing based on the idea you can sell the security at some higher price, at some point in the future, to some “greater fool”). In Law’s case, the proliferation of bank notes produced inflation that was out of control and caused capital to move out of France. Law was faced with the dilemma of whether to continue printing money to stabilize the share price of the Mississippi Company and risk hyperinflation or remove the excess money from the system and risk the bubble bursting. Law attempted to fix the share price at 9,000 livres, and again at 5,000 livres but it was not enough to revive the confidence in his system. He was sacked as finance minister and shareholders rushed to sell their shares to anyone who would buy them, at virtually any price, causing the share price to fall drastically and eventually crashing the entire French stock market.

In Chancellor’s words -

“Despite the fact that Law’s policies produced a surge of inflation and a great stock market crash, Ivy League academics warmly applaud his monetary notions. Peter Garber, a professor of economics at Brown University, claims that Law’s credit theory ‘is the centerpiece of most money and macroeconomics textbooks produced in the last two generations and the lingua franca of economic policymakers concerned with the problem of underemployed economics’. Garber believes that Law’s System had every chance of success. William Goetzmann of Yale credits Law’s belief that too little money constrains economic activity as ‘the essential principle underlying the decisions by the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank today’.

The collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 produced economic and financial conditions – a toxic mixture of deflation, high unemployment and soaring government debt – somewhat similar to France’s after the death of Louis XIV. Monetary policymakers responded to these conditions by taking a leaf from Law’s copybook, pushing down interest rates and acquiring large chunks of their national debt (although not going quite so far as Law) with newly printed money. There’s another similarity. After 2008, the Federal Reserve embarked on a deliberate policy of boosting asset prices by reducing the discount rate. While Law created Mississippi millionaires, his twenty first century imitators minted billions by the score."

So what happened next? Were there valuable lessons learned and efforts taken to prevent future manias and crashes? Well, yes. Were these efforts successful in curing the financial world of these drastic highs and lows? Well, not exactly. In fact, this framework of low rates driving people into speculative assets, other market participants feeling the fear of missing out and aping into the same assets, further bidding up the prices continued in many different eras in various locations, and played all almost exactly the same way every time. The bubble could last for a good while but eventually, inflation would begin to run hot, the central bank would be forced to raise interest rates and reduce the money supply in order to burst the bubble and often it would send the entire market crashing and the economy into a financial crisis. One took place in 1720 in London (the South Sea bubble). A building boom in the 1760s occurred in London after rates were lowered to 3.5 percent, only to come crashing down after the failure of Ayr Bank ( a Scottish Bank) which then triggered an international banking panic that would bring down Clifford & Sons (in Amsterdam) and further exacerbate the issues in London. In 1825, as yields on British Government Debt (called “consols” at the time) fell, clients from banks withdrew their money to invest in speculative projects. Banks lent against securities and mortgages (sound familiar?) and lent to builders with little and sometimes no track record.

William Bagehot, editor of The Economist, observed this behavior and attributed the speculative nature of these manias to interest rates that were too low.

“As a banker and financial journalist, Bagehot observed that outbreaks of financial recklessness did not occur at random. Rather, they tended to appear at times when money was easy and interest rates low. He expressed this insight in his own inimitable fashion: ‘John Bull can stand many things, but he cannot stand two per cent.’14 When interest rates fell to such a low level, investors reacted to the loss of income by taking greater risks. In modern language, they engage in ‘yield-chasing’. John Bull – that personification of English common sense – made his first appearance in Bagehot’s writings in an article for the Inquirer published on 31 July 1852:

‘John Bull’, says someone, ‘can stand a great deal, but he cannot stand two per cent …’ Here the moral obligation arises. People won’t take 2 per cent; they won’t bear a loss of income. Instead of that dreadful event, they invest their careful savings in something impossible – a canal to Kamchatka, a railway to Watchet, a plan for animating the Dead Sea, a corporation for shipping skates to the Torrid Zone. A century or two ago, the Dutch burgomasters, of all people in the world, invented the most imaginative occupation. The speculated in impossible tulips."

Bagehot wrote extensively about this phenomenon.

“While Overstone elaborated the phases of the credit cycle, Bagehot looked into its causes. The cycle arose, he said, from ‘the different amounts of loanable capital which are available at different times for the supply of trade’. Any number of reasons might cause the amount of loanable capital to vary – a gold discovery, the excessive issue of banknotes or the expansion of trade. But there was also a psychological element. ‘Credit, the disposition of one man to trust another, is singularly varying,’ Bagehot wrote. Interest is the barometer of trust, rising and falling over the course of the cycle. Too much trust is a dangerous thing. Bagehot described the lax financial behaviour that typified the peak of the credit cycle:”

“The good times, too, of high price almost always engender much fraud. All people are most credulous when they are most happy; and when much money has just been made, when some people are really making it, when most people think they are making it, there is a happy opportunity for ingenious mendacity.

As the cycle entered its final stages, the Bank of England would be forced to raise rates. The important thing, said Bagehot, was that it should act promptly. Bad lending had to be nipped in the bud. ‘The best method – the sole method – to contract the entire credit currency in this or in any other country is to raise the rate of interest.’ If the Bank failed to act in a timely fashion, a crisis became inevitable. During a panic trust evaporates and interest rates soar. After a prolonged period of high rates, however, ‘business is checked, prices fall [deflation], the exchanges are righted, and the balance of trade redressed.’ Once the panic has passed, capital lies idle and savings accumulate, and the supply of loanable capital exceeding demand for loans brings the rate of interest to a low point.”

The South Sea bubble took place after rates on Consols fell from 8 percent to 4 percent. After rates fell below 3 percent in 1790, a “canal mania” (investments in new canals) took place that ended in a banking crisis in 1793. Speculation in emerging markets took place in the early 1800s leading to another crisis in 1810 when a third of all the banks in England failed. In the 1840s, rates at 2 percent preceded a speculative mania in railroad investments. This eventually popped when “discount houses” (early commercial paper lenders) went bust. This caused Bagehot to reflect further and suggest the crucial idea that the central bank become a “lender of last resort.”

“To that end, he recommended that during a panic the Bank of England should lend copiously against good securities and at a high rate of interest.

Bagehot was not the first to suggest that the central bank had a responsibility to act as lender of last resort. That honour belongs to an English banker from an earlier generation. ‘Credit,’ wrote Sir Francis Baring, the head of the family banking firm, in 1797, ‘ought never to be subject to convulsions.’ Baring was writing after the failure of the Newcastle banks, brought about by the collapse of the canal mania. The Bank of England had taken fright and allowed the panic to fester. This was a mistake, said Baring: ‘there is no resource on their refusal, for they are the dernier resort.’ Baring’s contemporary Henry Thornton agreed that it was the Bank’s duty to provide credit during panics – then known as ‘internal drains’ – which were times when money was hoarded. John Fullarton compared the Bank to a ‘vast national granary’ to which in times of crisis the community was entitled to resort for succour."

I think it’s worth sharing the stories of Bagehot and the crises of Part 1 of the book (and so much of the original text) because they highlight what I believe to be crucial to Chancellor’s work - understanding where these ideas come from. Credit, Interest, Money, Central Banking and Monetary Policy are complex topics and it can be easy to feel overwhelmed when learning about them. Chancellor does a phenomenal job of documenting relevant historical events and tracing the lineage of important ideas.

“The Bagehot rule is much cited by monetary policymakers in the twenty-first century. After the 2008 global financial crisis, US Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner, a former President of the New York Federal Reserve, referred to Lombard Street as the ‘bible of central banking’. In his memoirs, The Courage to Act, Geithner’s former boss, Ben Bernanke, mentions Bagehot more frequently than any other economist. When Bernanke’s Federal Reserve and other central banks stepped up as lenders of last resort during the crisis, Bagehot provided the cover for their trillions of dollars’ worth of central bank loans.”

Despite Bagehot’s keen observations and diligent call to action, speculative manias would continue throughout the 19th century and would all inevitably end in banking crises and financial panics. A quote from Bagehot himself -

“the human mind likes 15 per cent; it likes things which promise much, which seem to bring large gains very close, which somehow excite sentiment and interest the imagination. The manufacturers of ‘financial schemes’ know this, and live by it. A long and painful experience is necessary to teach men that ‘15 per cent’ is dangerous; that new and showy schemes are to be distrusted; that the popular instinct on them is essentially fallible, and tends to prefer the brilliant policy above the sound – that which promises much and pays nothing, above that which, promising but little, pays that little.”

The final chapter of Part 1 deals with the run up to and the aftermath of the Great Depression. It presents a crucial idea put forth by Friedrich Hayek that challenges the Federal Reserve’s mandate of pursuing “price stability".

“When interest is determined in a free market, he said, time preference and the return on capital should equalize. The danger comes when the authorities interfere with interest rates. When interest rates are pushed too low, credit takes off and bad investments (‘malinvestment’) abound.

The Austrians embraced the concept of a natural rate of interest but disagreed with Wicksell that it could be divined simply by observing changes in consumer prices. For a start, they were sceptical of the very notion of a consumer price index. As one of their number, Oskar Morgenstern, commented, ‘the idea that as complex a phenomenon as the change in a “price level”, itself a heroic theoretical abstraction, could at present be measured to such a degree of accuracy is nevertheless simply absurd.’ And even if the consumer price index could be measured, the Austrians still didn’t believe that central bankers should aim to stabilize the price level.”

“In 1927, Hayek was appointed the first director of the Austrian Institute for Business Cycle Research, having previously studied monetary policy in New York. Hayek thought that the policy of price stabilization – as advocated by Irving Fisher and others and implemented by Ben Strong at the Federal Reserve – was misguided, and lamented that Fisher’s Stable Money Association (a successor to the Stable Money League) had turned the ‘concept of price stabilization as the objective of monetary policy into a virtually unassailable dogma’.

“In a capitalist economy, Hayek said, continuous advances in productivity mean that consumer prices have a natural tendency to decline. During periods of rapid technological development and commodity gluts, such as the 1920s, the price level might be expected to decline quite rapidly. The pursuit of stable prices by central bankers, however, worked against this natural tendency. Monetary policy directed at stabilizing prices, said Hayek, ‘administers an excessive stimulus to the expansion of output as costs of production fall, and thus regularly makes a later fall in prices with a simultaneous contraction of output unavoidable.’ The future Nobel laureate wrote these words in 1928. In effect, Hayek was predicting that the Roaring Twenties would end in a deflationary bust.

In his book Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle, published in German in the year of the Crash, Hayek criticized the Federal Reserve, which he accused of setting interest below its natural rate. The Fed’s error did not show up in the overt inflation of consumer prices, as Wicksell suggested. Instead, Hayek alluded to a hidden or ‘relative inflation’, accompanied by destabilizing credit growth and malinvestment. Advocates of stable prices, said Hayek, failed to understand the function of capital and interest."

“If accuracy of prediction is what matters for economic theory, as Milton Friedman later claimed, then Hayek’s interpretation should have become the received wisdom of his profession. Yet the Austrian’s interpretation of the 1920s and its aftermath has been more or less air-brushed from the history books, while Fisher’s monetarist view has become received wisdom.”

In the interest of brevity, I’ll quickly go through the high level topics covered in parts 2 and 3 of the book. If you enjoyed the summary of Part 1, I can almost promise you will enjoy the entire book. Chancellor has the enviable skill of being able to write about a complex topic in a way that is both educational and entertaining. He goes into a great amount of detail without being overly academic and presents vivid recollections of historical anecdotes that leave the reader feeling immersed in the stories he tells. If you enjoy financial history, you will love the book or if you would like to understand where the ideas that have shaped modern monetary policy came from, I can’t recommend “The Price of Time” enough.

Examples from Part 2

The second part of the book is concerned with modern financial crises, the monetary policy responses that followed and how economies fared in the aftermath of a severe boom/bust cycle. Part 2 documents the challenges Volcker had to go through in order to battle inflation that appeared to be getting out of control in the 1980s. It discusses the bubble economy of Japan in the 1990s and how the lowering of interest rates was not sufficient to jumpstart a stagnant economy out of a “balance sheet recession.” As an aside, if that topic is of interest to you, Richard Koo wrote a phenomenal book titled “The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics” where he examines the Japanese bubble and it’s aftermath in great detail. I wrote a brief thread summarizing my thoughts after reading the book.

https://twitter.com/netcapgirl/status/1603814904699535384?s=20

Part 2 discusses Alan Greenspan’s policy in the 1990s, the tech bubble of the late 90s and it’s inevitable bursting in the early 2000s. It discusses the forming of the credit bubble in the early 2000s when rates where held below levels of economic growth. It extensively covers the policy response to the great financial crisis in 2008 and questions why the US central bankers did not see it coming. The second part of the book references William White and Claudio Borio, chairs of the Bank of International Settlements (the central bank for central banks) and their criticism of modern central bankers inflation with lower interest rates and how they question their formal inflation targets, channeling Hayek in their wariness about the potential perils of pursuing price stability. Part 2 discusses the topic of “secular stagnation” or why modern developed economies have had trouble reaching productivity levels they had seen in the past and presents modern economists including Larry Summers views on the matter. Chancellor discusses what he believes are the downsides of rates held at artificially low levels (as it would appear is the case post 2008) and points out examples such as rampant financial engineering (loading up on cheap debt to fund buybacks that mainly serve to inflate EPS numbers that are the benchmark for executive compensation in many publicly traded companies), cash flow going to excessive risk taking instead of “real” investment (just like in manias past) and how the search for yield created the modern “everything bubble” we saw in 2020/21. He discusses the different form of risks - duration, liquidity and volatility risks that are present in securities markets and how low rates hurt savers and have “broken the social contract for workers hoping to have a comfortable retirement” to quote Big Short legend Michael Burry. It discusses the Eurozone crisis, negative rates and perhaps most harrowingly, the widening levels of inequality taking place in the modern world which Chancellor believes is a direct product of interest rates being too low. Chancellor touches on it briefly, but I do wish he would have further explored the link between low rates, widening wealth inequality and the rise of authoritarianism and populist politics.

Examples from Part 3

Part 3 of the book examines the global implications of the dollar standard (the US dollar being the world’s reserve currency) how it affects global capital flows and liquidity and what it means for emerging markets. It includes a vivid recollection of the events that led to the Arab Spring and is certainly an enlightening perspective from which to view how different geopolitical events have unfolded. It documents the “taper tantrum” and how it led to chain reaction in emerging markets and examples of how it affected their economies such as in Turkey. It examines how interest rates affect capital flows and what that means for globalization and trade wars and discusses “financial repression” (savers earning rates below the rate of inflation) in China. The book concludes with more from Friedrich Hayek and his rejection of central planning from his book “The Road to Serfdom”.

“The Road to Serfdom was directed at the unintended consequences of centralized economic policymaking. ‘[W]e may choose the wrong way,’ Hayek wrote in the Introduction, ‘not by deliberation and concerted decision, but because we seem to be blundering into it.’ Hayek was skeptical about the mindset of central planners, scientists and engineering types whose ‘habits of thought … tended to discredit the results of the past study of society which did not conform to their prejudices’. He rejected the notion that planning should be taken away from politicians and put in ‘the hands of experts – permanent officials or independent autonomous bodies’. Even technocrats had interests, and, left to their own devices, they would impose their preferences on the community.”

“Central planning doesn’t work, in Hayek’s view, because public officials can never gather all the information needed to make it work. On the other hand, capitalism works because it is a system in which decision-making is decentralized: prices set under competitive conditions contain all the information about people’s infinitely varied preferences. Hayek refers to ‘regulation by the price mechanism’. If resources aren’t allocated by the market then the authorities must step in. He was concerned that ‘once the free working of the market is impeded beyond a certain degree, the planner will be forced to extend his controls until they become all-comprehensive.’

In The Road to Serfdom, Hayek warns against official attempts to achieve full employment through monetary policy, which he believed would damage growth prospects. He also rejects policies directed at ironing out economic fluctuations and underwriting market risks:

the more we try to provide full security by interfering with the market system, the greater the insecurity becomes; and, what is worse, the greater becomes the contrast between the security of those to whom it is granted as a privilege and the ever increasing insecurity of the underprivileged.”

“Under a central-planning regime, he predicted, people would seek security instead of independence, while ‘insecurity becomes the dreaded state of the pariah.’ Regulation, he feared, would serve the interests of the powerful at the expense of everyone else.34 The economist-philosopher fretted about how inequality would be perceived under central planning: ‘Inequality is undoubtedly more readily borne, and affects the dignity of the person much less, if it is determined by impersonal forces than when it is due to design.’35 Political stability, in Hayek’s view, depends on the existence of a strong middle class: ‘the one decisive factor in the rise of totalitarianism on the Continent,’ he wrote, ‘is the existence of a large recently dispossessed middle class”

Though a sober (and at times harrowing) read, the book ends on a hopeful note by documenting what Chancellor calls “The Icelandic Counterfactual” - Iceland’s policy response to the great financial crisis.

“Unlike several other central banks, the Icelandic Central Bank (ICB) didn’t receive dollar swaps from the Federal Reserve. There was no quantitative easing or interest-rate cuts. Instead, after the krona collapsed on the foreign exchanges (losing around half its value relative to the dollar), inflation took off. Capital controls were imposed in 2009 to stop money from leaving the country. The ICB was forced to raise interest rates, which later peaked at 18 per cent. Iceland received emergency loans from the IMF and Scandinavian neighbours and, in return, swallowed the bitter medicine of austerity. Savings went up. Consumption went down. Taxes were raised. Government spending was cut.”

“The financial sector didn’t contribute to Iceland’s recovery but continued shrinking. Instead, new growth came from a variety of sectors: tourism, renewable energy and technology. While the rest of the developed world was engulfed in an intractable pensions’ crisis, Iceland’s private retirement savings comfortably exceeded national income. A decade after the crisis, Iceland’s GDP was 15 per cent above its pre-crisis peak – a better performance than in most of the developed world. In 2018 Iceland claimed seventh place in the OECD’s ranking of output per capita, up four places since 2007. As the economy shifted away from finance it became more diversified. As debt levels declined, they became more sustainable. During the crisis, Iceland’s unemployment rate hit 9 per cent – around the same level as that of the United States. But unemployment soon fell back to its average level. As for inequality, Iceland’s Gini coefficient for incomes declined after 2008.”

Whether or not you agree with Chancellor “The Price of Time” is a fascinating read and presents complex ideas in an approachable way and leaves the reader capable of engaging with the long lineage of ideas about credit, money and interest that have shaped our modern world. There is certainly another side to this argument, referred to in modern central banker parlance as “TINA” or “there is no alternative” but that view is far more popularized in the current zeitgeist and therefore Chancellor is doing extremely important work by putting together ideas meant to challenge such a popular and powerful narrative. I hope you enjoyed my review/summary of this wonderful book and I’d love to know if it inspired you to read it. Please don’t hesitate to reach out on twitter with your thoughts, feedback or suggestions about what you’d like to see me write about in the future!

I thought I was the unsung master of the long-form book review. Actually, you are. I know when I'm licked.

Here's my review of The Price of Time. https://larrysiegel.org/the-price-of-time/

Interest rates are fun to think about.

That wasn't always the case, but after investing for a couple of decades and buying/selling individual stocks for a few years now, I've finally started to feel like the knowledge is "intuitive" for me. It's automatic: if the Fed lowers rates, the market gets all kinds of excited... and it's easy for me to see why.

I need to go check out this book now.