Inevitability Weekly #3

OpenAI, Consumer Earnings, Peter Thiel Interview and more

OpenAI and Government Support

All eyes were on OpenAI CFO Sarah Friar this week as she spoke about the US Government potentially becoming more involved in funding AI development. At the Wall Street Journal’s Tech Live Conference she said the following that then made waves around the internet.

“This is where we’re looking for an ecosystem of banks, private equity, maybe even governmental, the ways governments can come to bear,” she said. “The backstop, the guarantee that allows the financing to happen, that can really drop the cost of the financing but also increase the loan-to-value, so the amount of debt you can take on top of an equity portion.”

She would later follow up with a LinkedIn post saying:

I want to clarify my comments earlier today. OpenAI is not seeking a government backstop for our infrastructure commitments. I used the word “backstop” and it muddied the point. As the full clip of my answer shows, I was making the point that American strength in technology will come from building real industrial capacity which requires the private sector and government playing their part. As I said, the US government has been incredibly forward-leaning and has really understood that AI is a national strategic asset.

Sam Altman later followed up in a tweet saying:

I would like to clarify a few things.

First, the obvious one: we do not have or want government guarantees for OpenAI datacenters. We believe that governments should not pick winners or losers, and that taxpayers should not bail out companies that make bad business decisions or otherwise lose in the market. If one company fails, other companies will do good work.

What we do think might make sense is governments building (and owning) their own AI infrastructure, but then the upside of that should flow to the government as well. We can imagine a world where governments decide to offtake a lot of computing power and get to decide how to use it, and it may make sense to provide lower cost of capital to do so. Building a strategic national reserve of computing power makes a lot of sense. But this should be for the government’s benefit, not the benefit of private companies.

The one area where we have discussed loan guarantees is as part of supporting the buildout of semiconductor fabs in the US, where we and other companies have responded to the government’s call and where we would be happy to help (though we did not formally apply). The basic idea there has been ensuring that the sourcing of the chip supply chain is as American as possible in order to bring jobs and industrialization back to the US, and to enhance the strategic position of the US with an independent supply chain, for the benefit of all American companies. This is of course different from governments guaranteeing private-benefit datacenter buildouts.

Which was followed by the post receiving a community note with a quote from OpenAI’s letter to the government:

“To provide manufacturers with the certainty and capital they need to scale production quickly, the federal government should also deploy grants, cost-sharing agreements, loans, or loan guarantees to expand industrial base capacity and resilience.”

A thoughtful tweet from Dean Ball shed some helpful light on the situation:

4. In an, again, entirely separate public interest comment submitted to the White House (downstream of a request for information that, incidentally, I drafted while I was in government) late last month, OpenAI discussed broadly the notion of reducing the cost of capital for manufacturers in the AI data center supply chain. We already do this for semiconductor manufacturing through the CHIPS Act.

5. Lowering the cost of capital for manufacturers of strategic goods is not at all a “loan guarantee.” Consider natural gas turbines. That industry has gone through brutal boom and bust cycles in recent decades. If you run a natural gas turbine manufacturer, or are a long-term investor in one, or loan money to such firms, you are going to be weary of too much expansion for fear that the AI bubble will pop. This slows down supply expansion for a good that we really do need to power AI in the near term. So what do you do?

6. Well, one thing you could do is have the federal government serve as buyer of last resort of future turbines. You write a contract that says “if the manufacturer makes X turbines over the next five years, the federal will pay Y price for Z number of turbines if no other private-sector buyer emerges at or above price Y.” That way, the manufacturer can go to its investors and lenders and say, “don’t worry, we’ve got a buyer for turbines if we expand.” And perhaps the lender is willing to offer the manufacturer a lower rate of interest--a lower cost of capital. I myself advocated for precisely this policy when I worked for the Trump Administration (though it didn’t make it into the AI Action Plan, sadly). There are many, similar schemes one could imagine.

7. This idea involves the government taking limited, pre-defined risk. The political economy problems with this are non-zero, but they are far smaller than the regulatory capture that would ensue from the US government guaranteeing untold billions of OpenAI debt.

8. As I read OpenAI’s public interest comment, I interpret them to have been talking much more about the kind of thing I describe in item (6) rather than the loan guarantee for OpenAI debt. They are referring them to manufacturer cost of capital in that comment; I don’t think OpenAI refers to itself as a “manufacturer.”

What to make of all of this? For one, at a meta level, OpenAI’s dominance of the finance and tech press surrounding AI has seemed to serve to make the company synonymous with AI in the mind of the public. One word from their CFO created global headlines.

But at a deeper level I think the story reflects something more important and that is that AI is now unquestionably a national strategic industry and inevitably, the US government will play an increasingly important role in the AI supply chain.

At a cursory glance, I would tend to agree with the sentiment that their CFO misspoke and the term “backstop” was the wrong word for the suggestion that the government was going to become increasingly involved in the AI arms race. As Dean points out, industrial strategy at a national level to lower manufacturer’s cost of capital would make sense for one since AI is becoming increasingly a national security issue, and also because the downstream effects, such as more manufacturing, more electricity producing assets, a better power grid etc., will hopefully help the American people in different ways for the foreseeable future. The cynical read is that of course regulatory capture is a potential strategy for the various companies involved at the frontiers of AI and the situation is certainly one to monitor.

On another note, Friar said that there are no near term plans for OpenAI to IPO. One could argue that more valuable startups going public would be a net positive for Americans who have a portion of their wealth invested in domestic stock indices. But with their aggressive spending plans, they seem to be waiting until they reach a more mature stage financially, with revenue growth and margins that would satisfy investors in a public offering (though there is little doubt that OpenAI would be one of the biggest IPOs of all time.)

All of this speaks to the scale of the capital required to build the future. But another part of the picture is how consumers are behaving right now, and earnings this quarter paint a more complicated story

Consumer Earnings

Every earnings season is a lens through which investors attempt to understand the broader macro environment. While tech earnings have focused attention on future capex, model training cycles, and the AI infrastructure race, the consumer side of the economy tells a different story. Investors are looking closely at restaurant chains, delivery platforms and consumer brands to diagnose the underlying health of household spending.

For instance, many are calling “peak slop bowl” as Chipotle, Cava and Sweetgreen all disappointed investors and saw their stocks drop.

Chipotle reported third quarter revenue of about $3.0B, up 7.5% year over year, but same store sales increased only 0.3% versus expectations of roughly 0.7%. Restaurant level operating margin fell to 15.9% from 16.9% a year ago. The stock dropped as much as 19% following the release.

Cava reported revenue of $289.8M, up 20% year over year, and same restaurant sales growth of 1.9%. Even with earnings of $0.12 per share versus estimates of roughly $0.11, the stock declined about 2% after the call. Investors focused on slowing traffic and cautious guidance.

Sweetgreen reported revenue of about $172M, down 0.6% year over year. Same store sales declined 9.5% and traffic fell 11.7%. Full year guidance was cut to a revenue range of $682M to $688M with a same store sales decline of 7.7% to 8.5%. The stock declined around 8% in response.

Door Dash fell 17% following its third quarter report. Revenue grew 27% year over year to $3.4B and total orders grew 21%, but EPS came in at about $0.55 versus estimates of roughly $0.68. Rising costs, higher planned spending in 2026 and questions about unit economics drove the negative reaction.

Celsius produced one of the most dramatic moves. Revenue of $725M represented growth of more than 170% year over year, and non GAAP EPS came in at $0.42. Despite the strong headline numbers, the stock fell more than 20% due to concerns about distribution channel changes and near term margin risk.

McDonald’s reported third quarter revenue of $7.08B, slightly below estimates, and EPS of about $3.18 compared to expectations of $3.33 to $3.35. Comparable sales grew 3.6% globally and 2.4% in the United States. The company highlighted persistent weakness among lower income consumers and a widening gap between high income and low income spending patterns.

e.l.f. Beauty reported quarterly revenue of $343.9M, up 14.2% year over year, but short of analyst expectations of roughly $367.9M. EPS came in at $0.68 versus estimates near $0.57. Despite the EPS beat, forward guidance disappointed and the stock fell more than 20% in after hours trading.

Toast reported revenue of $1.55B, up 24.8% year over year, and net income of $0.13 per share. The company continues to grow at a strong rate, but results relative to expectations have been mixed across recent quarters. While revenue growth was solid, the stock move was limited as investors looked for clearer signs of sustained operating leverage.

Uber reported solid operating results with revenue of $13.5B, up 20% year over year, and adjusted EBITDA growth of more than 30%. Monthly active consumers grew 17%. Even with strong reported numbers, the stock reaction was muted because gross bookings guidance for the next quarter came in toward the low end of expectations.

Robinhood was one of the few bright spots. The company reported revenue of $1.27B versus expectations of about $1.19B and EPS of $0.61 versus estimates of $0.51. The stock rose about 4% after hours.

You can also see the market wrestling with two very different interpretations of these results. One argument is that fast food, especially fast casual, expanded too quickly and pushed prices beyond what consumers were willing to pay. As BuccoCapital (a great follow) pointed out, brands have been trying to raise prices while simultaneously becoming more commoditized. Toast reported higher gross payment volume per location, which suggests consumers are still eating out but are becoming far more selective.

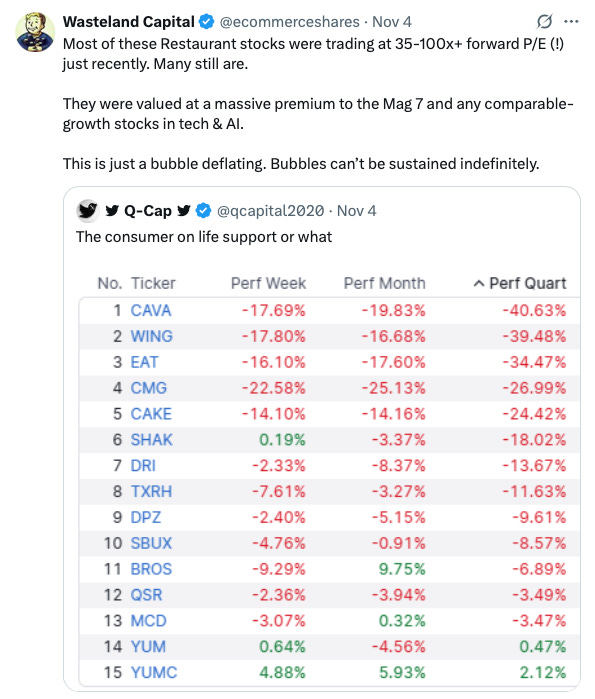

The other argument focuses on valuations. As Wasteland Capital (another great follow) pointed out many of these restaurant stocks were trading at forward price to earnings multiples of thirty five to one hundred times. They were priced at a premium even to the fastest growth names in tech and artificial intelligence. The recent declines may have less to do with a sudden deterioration in the consumer and more to do with a bubble deflating.

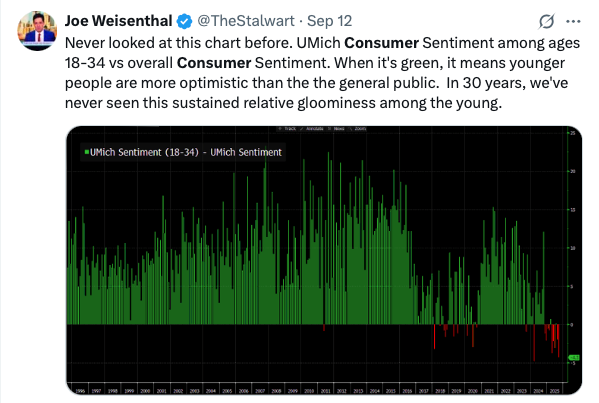

You can also see this pressure reflected in consumer sentiment data. Recent University of Michigan numbers show that sentiment among Americans ages eighteen to thirty four is now significantly more negative than the general population. Historically, younger people are more optimistic, but over the past few years the relationship has flipped. As Joe Weisenthal (yet another amazing follow) noted in September, in thirty years of data we have never seen such a sustained period of relative gloom among the young.

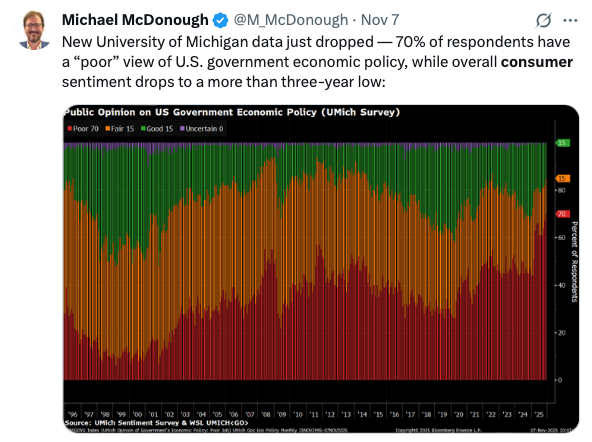

Broader sentiment is weakening as well. New University of Michigan survey data shows that about seventy percent of respondents have a poor view of current United States government economic policy. Overall consumer sentiment has now fallen to its lowest level in more than three years. This is consistent with what companies are reporting in their earnings calls. Consumers are still spending, but they are becoming more selective, more price sensitive and more skeptical of economic conditions

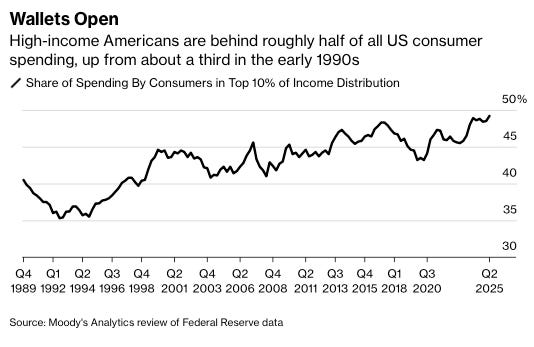

As Bloomberg reported in September, the top 10% of earners account for half of all spending.

This lends credibility to the idea that we’re in a “K-shaped” economy. Per Lisa Shalett at Morgan Stanley:

“Decoding this conundrum may hinge on the so-called K-shaped economy,” she wrote, “a concept that captures the widening chasm between the ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots.’”

Then Shalett said the situation is actually even worse than what Zandi produced: “For the U.S. consumer, wealth concentration has produced a situation where the top 40% of households by income account for approximately 60% of all spending; those households, in turn, control nearly 85% of America’s wealth, two-thirds of which is directly tied to the stock market, which has climbed more than 90% in three years.” She calculated that spending by the wealthiest households was growing 6x-7x faster than for the lowest cohort.

Even Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell talked about seeing the pattern at October’s Federal Open Market Committee meeting. “If you listen to the earnings calls or the reports of big, public, consumer-facing companies, many of them are saying that there’s a bifurcated economy there and that consumers at the lower end are struggling and buying less and shifting to lower cost products,” Powell said last week. “But at the top, people are spending, at the higher income and wealth.”

The idea of a K shaped economy has many interesting implications for markets moving forward but beyond just markets, one wonders what this may mean for culture and politics. These points feel particularly relevant when viewed alongside the current macro data.

Peter Thiel Interview

Peter Thiel gave a thoughtful interview with The Free Press about how he sees the current political environment. He highlighted student debt and housing as two major drivers of why so many young people are becoming disillusioned with capitalism. Points that definitely feel relevant to understand against the current backdrop of macro data.

If you graduated in 1970 with no student debt, compare that to the millennial experience: too many people go to college, they don’t learn anything, and they end up with incredibly burdensome debt. Student debt is a version of this generational conflict that I’ve talked about for a long time.

The rupture of the generational compact isn’t limited to student debt, either. I think you can reduce 80 percent of culture wars to questions of economics—like a libertarian or a Marxist would—and then you can reduce maybe 80 percent of economic questions to questions of real estate.

He had written the below email in 2020, urging the leadership team at Facebook to take a serious look at what was driving a growing interest in socialism.

There are many themes that could be developed more here; let me make a few quick points for now:

Nick -- I certainly would not suggest that our policy should be to embrace Millennial attitudes unreflectively. I would be the last person to advocate for socialism. But when 70% of Millennials say they are pro-socialist, we need to do better than simply dismiss them by saying that they are stupid or entitled or brainwashed; we should try and understand why. And, from the perspective of a broken generational compact, there seems to be a pretty straightforward answer to me, namely, that when one has too much student debt or if housing is too unaffordable, then one will have negative capital for a long time and/or find it very hard to start accumulating capital in the form of real estate; and if one has no stake in the capitalist system, then one may well turn against it.

When asked where to look for answers, in typical Thiel fashion he suggests the solutions may lay outside the Overton Window

So the idea is: Maybe we should look for solutions outside the Overton Window. And that includes some very left-wing economics, socialist-type stuff. I don’t think those ideas will ultimately work, but they’re more than whatever was on offer. Cuomo did not have a plan for housing. He didn’t even think it was an issue. And of course, he’s been in politics and government for many, many years, so it’s hard not to ask: Why is he going to do something now, if he hasn’t done anything before? So, I’m not optimistic about Mamdani, but if you score it relatively, this is the kind of thing that’s going to happen if you look outside the Overton Window for solutions.

It is always interesting to hear what Peter Thiel has to say, and his comments feel especially relevant to the sociopolitical climate we find ourselves in today. With pessimism toward capitalism rising, gambling surging in popularity, and this weekend’s conversations about stimulus checks and fifty year mortgages, it feels useful to understand the cultural and economic forces shaping this moment. There are extrapolations to be made about future economic and market trends, but even beyond that, it helps to have a clearer sense of what people are responding to in a period that can feel increasingly tense and polarized.

Roundup

There was a lot happening this week. Here are a few more pieces that I found interesting

A fascinating look at what it’s like inside Cursor by Brie Wolfson. Another brilliant piece from Colossus.

Compelling Mission + Hardcore Technical Problems + Winning + Excellent Recruiting = Off-The-Charts Talent Density

Normally, the best talent doesn’t readily accrue to a company so early in its life. But because Cursor has all the magic ingredients, it could hire exceptional people from the outset.

On the product and engineering side, Cursor is building at the intersection of the most interesting challenges in UX and machine learning. (The work on Cursor 2.0, including its own custom model and a new UI dedicated to agent work flows, is a recent testament). On the go-to-market side, Cursor is one of the fastest growing companies of all time from a revenue perspective—it went from $0 to $100mn ARR without a sales team, and the one that’s since been installed is determined to add another zero before the end of 2025. The #closed-won channel, in which a Slack bot alerts the company to newly closed sales victories, is a near-constant stream of notifications.

Tesla shareholders approved Elon Musk’s almost $1T pay package

The first tranche of stock gets paid out if Tesla hits a market capitalization of $2 trillion. Tesla’s current market cap is $1.54 trillion. Awards tied to market cap gains are paired with operational achievements.

The next nine tranches would be awarded if Tesla’s value increases by increments of $500 billion, up to $6.5 trillion. Musk would earn the last two tranches if the market cap rises by increments of $1 trillion, meaning it would need to hit $8.5 trillion for Musk to get the full package.

Tesla also laid out a series of earnings milestones for Musk, beginning with $50 billion in annual adjusted profit and moving up to $400 billion. In the third quarter, Tesla reported adjusted EBITDA of $4.2 billion.

Other goals tied to the newly approved pay plan include reaching 20 million vehicle deliveries, 10 million active FSD (Full Self-Driving) subscriptions, 1 million bots (Optimus humanoid robots) delivered and 1 million robotaxis in commercial operation. To date, Tesla has delivered more than 8 million vehicles, according to its September proxy statement.

Elon also mentioned that Tesla may need to build their own chip fab

“But even when we extrapolate the best-case scenario for chip production from our suppliers, it’s still not enough,” he said.

Tesla would probably need to build a “gigantic” chip fab, which Musk described as a “Tesla terra fab.” “I can’t see any other way to get to the volume of chips that we’re looking for.”

According to Musk, Tesla’s potential fab’s initial capacity would reach 100,000 wafer starts per month and eventually scale up to 1 million. In the semiconductor industry, wafer starts per month is a measure of how many new chips a fab produces each month.

For comparison, TSMC says its annual wafer production capacity reached 17 million in 2024, or around 1.42 million wafer starts per month.

While Tesla doesn’t yet manufacture its own microchips, the company has been designing custom chips for autonomous driving for several years.

It is currently outsourcing production of its latest-generation “AI5” chip, which Musk said will be cheaper, power-efficient, and optimized for Tesla’s AI software.

“With AI and robotics, you can actually increase the global economy by a factor of 10, or maybe 100. There’s not, like, an obvious limit,” Musk said at the shareholder meeting.

An interesting Wall Street Journal piece about the “end of the microchip era” by George Gilder

You can see the effects of the reticle limit in the ever-mounting complexity of Nvidia-defined vast hyperscale data centers. The result—smaller, denser chips and “chiplets,” each with its own elaborate packaging—is a greater need for ultimate reintegration of the processes for coherent outcomes. The calculation first has to be dispersed among many chips, then recompiled. The effect is more communications overhead between chips requiring ever more complex packages, ever more wires and fiber-optic links.

The result of the inexorable reticle limit is the end of chips. What’s next? A wafer-scale integration model, which bypasses chips altogether. Mr. Musk pioneered this concept at Tesla with his now-disbanded Dojo computer project; the effort has been recreated as DensityAI.

Cerebras of Palo Alto, Calif., used the concept in its WSE-3 wafer-scale engine. The WSE-3 boasts some four trillion transistors—14 times as many as Nvidia’s Blackwell chip—with 7,000 times the memory bandwidth. Cerebras inscribed the memory directly on to the wafer rather than relegating it to distant chips and chiplets in high-bandwidth memory mazes.

Also working on a full wafer-scale future is David Lam, founder of Lam ResearchCorp., the world’s third-largest wafer-fabrication equipment company. In 2010, Mr. Lam founded Multibeam Corp., which created a machine that performs multi-column e-beam lithography. The technology allows manufacturers to bypass the reticle limit.

A new paper on capital allocation by Michael Mauboussin which is “a comprehensive study of how public companies in the U.S. spend money. We extend most of the analysis back to 1970, update the data through 2024, and discuss results for the first half of 2025 where practicable.”

A new Howard Marks memo

As always, thanks for reading. There will be more to come next week as we continue to focus on bottlenecks, thresholds and all the forces driving us toward inevitable futures.

Good stuff

Glad to see you posting again!